Have you ever had an idea for a project that mattered so much, it felt safer to imagine than to actually begin?

I’ve had a project like that haunting me for months. I’ve been telling myself I was waiting for the right time, the right clarity, the right energy. But really, deep down inside, I have been scared to death of screwing it all up—and today, I almost did.

I’ve had a rough day. Let me tell you about it.

Nine Uniforms, Twenty Years

I’m retiring from the Navy in just a few months, after 20 years of active duty service.

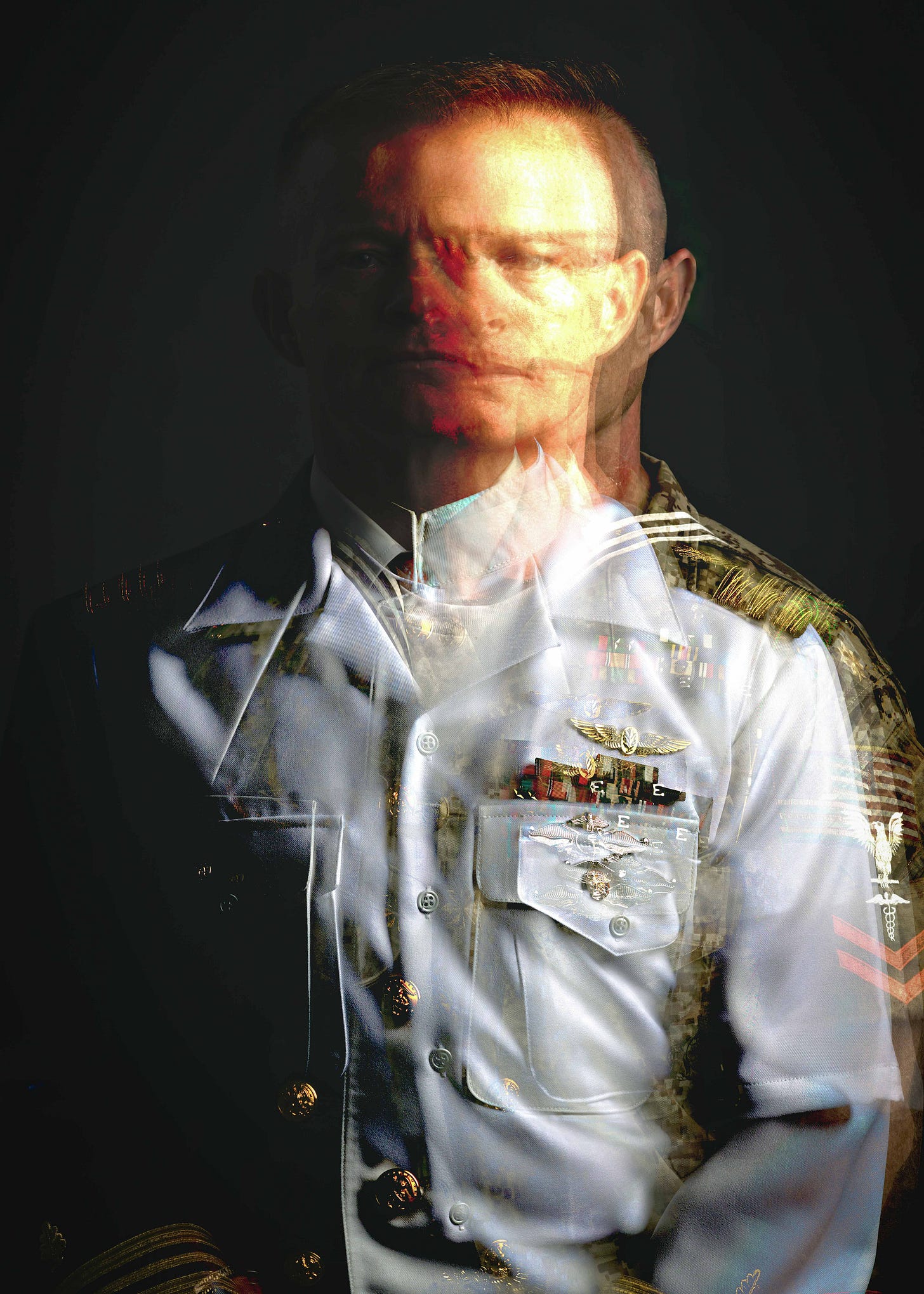

About a year ago, I had an idea for a project: I would take a photo of myself in every uniform I’ve worn—nine in total—and put them into some sort of collage. The concept was simple: a visual progression from the uniform I wore in boot camp to the one I’ll wear at my retirement ceremony—which is only one month away now.

So, this morning, I decided enough was enough. If I didn’t do this project now, it wouldn’t get done.

Years from now, I might not remember the cake or words spoken on my behalf from a retirement ceremony.

But I would always regret not taking the time to make this project happen.

So, with a reluctant but determined effort, I began this project just like any other—by putting one foot in front of the other.

The Weight of Cloth and Time

I started by removing all the uniforms from my closet and inventorying them. Hanger after hanger, I removed outfits and laid them on my bed. Their patterns and fabrics created a kaleidoscope of colors and textures, from shiny brass buttons and dark Navy blue tweed, to jungle digital camouflage. Surveying the assortment, I could see I was missing a few. What I had before me were only my most recent uniforms—the ones I still wore on a regular basis. But there were older ones that needed to be part of this project, too.

I enlisted in the Navy in April of 2005 and served seven years as a Fleet Marine Force Corpsman before commissioning in July of 2012. Officers and enlisted service members wear different uniforms, so after my commissioning ceremony, I packed all my enlisted uniforms into a vacuum storage bag and tucked them away in a plastic storage tub. I remember that day vividly.

I had orders in hand to Officer Candidate School, with follow on orders to Pensacola, Florida where I would begin flight training. Life was changing in remarkable ways, very quickly. My daughter—just six months old at the time—was crawling around my feet as I carefully folded and stacked each uniform. The iconic “Cracker Jack” dress blues. The blue utilities and coveralls I wore aboard ships. The USMC desert cammies I had lived and slept in for years downrange. I had worn all of these uniforms officially for the last time.

As I sealed the bag shut, I remember thinking the next time I wear these will probably be just before I retire. Just for the memories.

Even then, the seed of this project had already been planted.

So you can imagine what a surreal experience it was when I dug through my attic this morning and found that old tub. There were four moving stickers affixed to it, one for each duty station since packing it up. It was just moved from house to house. It had never been opened, until today.

I have had a strange love-hate relationship with uniforms throughout my career. At some times, I felt like they stripped me of identity and made me feel less like an individual and more like a robot. At other times, they have made me feel part of something larger than myself.

Don’t get me wrong, it has always been a privilege to serve in the military. But it is difficult to avoid feeling like part of the Borg collective at times, especially when watching other classmates and friends climb corporate ladders and grow into flourishing identities while I have had to shave my face and wear the same haircut for twenty years. But as much as those uniforms sometimes made me feel like a cookie cutter individual, there were also times when they represented something much more significant.

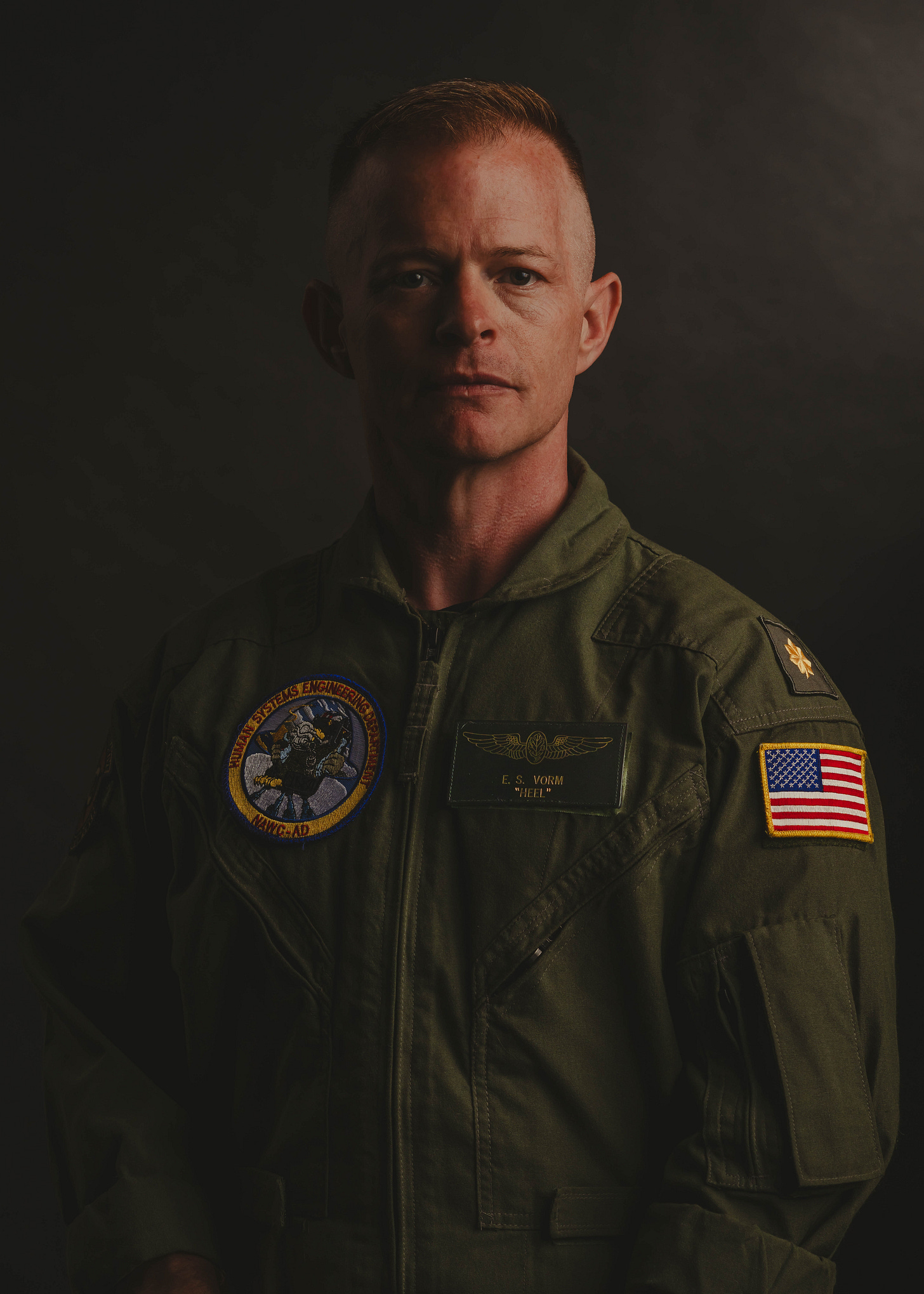

For example, when you begin flight training, you are not allowed to wear the flight suit until you pass all the academic tests of aviation preflight indoctrination (API). API is a grueling six-week course that moves extremely fast and takes no prisoners. Courses include subjects like aerodynamics, FAA rules and regulations, aviation weather, engines and hydraulics. It is like drinking from an academic fire hose, and is designed as the last milestone to weed out candidates before they actually begin learning how to fly airplanes. Tests are pass/fail, and happen Mondays of each week. If you fail once, you take the same test the very next morning, while also having to study the new material for that week.

If you fail twice, you’re out.

The morning of the last test is always a Friday. Grades are posted late in the afternoon. All those who pass their final test are officially allowed to wear a flight suit as the uniform of the day for the remainder of flight training. To celebrate, everyone dons their flight suits for the first time and heads to the Officer’s Club for happy hour. Instructors come and celebrate with the students. The event is officially known as “flight suit Friday.”

It is an amazing feeling to toast this early success, even while knowing that the real test hasn’t even begun yet. The immense pride of wearing that sacred and distinct uniform for the first time is beyond description.

There are countless other memories I could share, but you get the idea.

The Last Uniform

At the studio, I laid everything out and assembled all the accoutrements with the fastidious detail befitting a sailor who once stood uniform inspections, only to later become the officer who conducted them.

I moved slowly, almost ceremonially. My hands moved instinctively: smoothing wrinkles, aligning insignia. And as I did, I lapsed into a pleasant nostalgia. These weren’t just old clothes. They were chapters of my life. Part of my identity. They lived in the background of memories and photographs. And now, for the first time in more than a decade, I was bringing them back into the light.

It was a simple joy to try them on again and stand before the mirror.

I smiled at my own reflection, which looked much like it did twenty years ago—except for the lines etched near my eyes and the grey at my temples. I laughed and joked as, one after another, I donned each uniform and sat before the camera. I flexed in the mirror and indulged in a little pride at being able to wear in my mid-40s uniforms I first wore in my early 20s. It was good, lighthearted fun.

But as I took out the last uniform of the day, something unexpectedly shifted.

The last uniform I pulled out was my desert utility uniform, aka “cammies” from my seven years with the Marine Corps. The worn fabric had faded to a pale hue, bleached by years in the desert sun. The fibers had been softened by sandstorms of the Syrian desert—beaten into comfort by hardship and years of abuse.

Pulling it on, I could almost smell the diesel fuel, the MREs, the scorched metal. My shoulders settled into the posture I carried back then—alert, hard, a little cocky. But when I looked in the mirror, it wasn’t pride I saw.

It was something heavier.

I wore this uniform in combat. Not one like it—this exact one. The same cloth that clung to my body during convoys and raids. The same one I sweat through, bled into, slept in, prayed in.

Feeling it against my skin again—rolling the sleeves into place—brought the full weight of time crashing down. I realized how long it had been since I packed it away.

How long it had been since I packed that version of me away.

And suddenly, unexpectedly, I felt like I was tarnishing something sacred.

This uniform didn’t belong with the others. It carried something the others didn’t. It wasn’t just part of my story—it was the story. And standing there in the quiet of my studio, camera waiting, I felt shame rise up in my chest.

These were the clothes I wore in a completely different life. The person who wore them last… I’m not sure I ever said goodbye to him.

The last time I wore this uniform, some of my friends were still alive.

This wasn’t nostalgia anymore.

This felt like something else. It felt like violation. Or like a betrayal.

Some of those who stood beside me in these uniforms never got the chance to grow old. They never had a chance to lay out their uniforms, side by side, and relive the memories of 20 years. And somehow, I did.

Thoughts flooded my consciousness, making it impossible for me to focus on what I was doing. I was spiraling quickly, and I felt waves of emotion come over me like I hadn’t in years.

A profound sadness overtook me, and as tears escaped my eyes, old questions I hadn’t heard in years reemerged:

What would they do with this life if they had it?

Am I living in a way that honors the fact that I’m still here?

Would they be disappointed in me if they could see me now?

What am I supposed to do with this life?

These questions are familiar companions to anyone who lives with survivor’s guilt—a persistent feature of PTSD that rarely announces itself directly. It lingers just beneath the surface, always asking: Why me? Why did I make it home when others didn’t?

The Paradox of Healing

I read a lot about healing these days. My Substack feed is full of essays and notes. My shelves are stacked with books. I attend daily 12-step meetings and I talk to dozens of people about the topic each week.

And yet, despite all that, I still often wonder if I’m doing it right. If I’m doing enough.

The strange thing about healing is that it doesn’t bring us back to who we were. It’s not as much about restoration as it is about transformation. And transformation requires new structures: new patterns, boundaries, and ways of holding truth. Like the parable says: you can’t pour new wine into old wineskins.

Why not? Because the old container—our former ways of coping and thinking—was shaped by survival. It served its purpose, but it can’t hold what comes next. New wine is still alive, still expanding. It needs room to breathe.

That’s why healing often feels like breaking.

Because it is.

The old framework no longer fits.

And that’s the paradox: to heal, we often have to let go of things that once kept us safe.

And that is terrifying.

Transformation is disorienting. Some days I feel out of sync with myself, switching between who I was, who I am, and who I’m becoming.

Some people look back at their earlier selves with a sense of pride and continuity. They see a clear progression—each stage a stepping stone to the next. Growth feels linear, even logical: a gradual unfolding from simplicity to complexity, from novice to expert. Their past selves feel like younger siblings they’ve outgrown, but still recognize with affection.

For others, development is anything but linear. Wandering is part of the process. Growth involves a lot of breaking, bumping into things, and sometimes starting over.

For us, looking back can feel disorienting, often painful. Our past selves aren’t easily folded into a single arc. And the present moment—especially when it involves leaving old systems behind or stepping into the unknown—can bring with it fear, grief, and a deep sense of rupture.

That’s why, when I think about those who didn’t make it back, I often imagine them watching me from somewhere unseen, heads shaking in disappointment.

Because for some of us, guilt becomes the only compass we know. That’s why its called survivor GUILT. We imagine the dead as silent judges, holding us accountable for things we can never repay. When we look at ourselves and compare today to who we were, it can sometimes produce fear and disappointment, rather than pride.

But the fact is, I am not who I was in those cammies, or that Cracker Jack uniform anymore. Even these days when I wear my flight suit to work, I know the version of me a year from now will look very different, inside and out, than the person I am today. Living the way I live today isn’t forgetting the past. It’s honoring it by allowing myself to become.

And I love that person.

I don’t believe that is betrayal. I believe that is growth.

A Final Fold

Once home, with dinner served and the dishes washed, I retreated to my bedroom and began the process of returning these uniforms to their hangars. I packed the older ones back into the same vacuum bag, folding them along creases that had existed for the past 15 years. There was no six-month old crawling around my feet this time. No four-year old asking if I could read him a book. There was just me, in a quiet room, folding the cloth of our nation one last time.

As I put the uniforms away, I encouraged a new picture to play in my mind.

Instead of the guilt-inducing disappointing looks of my lost friends, I imagined one of my old friends who is no longer on this planet—a loud, irreverent Marine with a foul mouth and a penchant for chaos—standing just out of frame, arms crossed, a crooked grin on his face. He wasn’t shaking his head no. Instead, he was nodding with approval towards me. I heard his Alabama accent and deep gravely voice saying Hell yeah, brother. Look at you. Get it!

And with that vision in my head, I smiled to myself, shed a few more silent tears, and told myself that it is time to let go.

Because here’s the hard truth: guilt has no real wisdom to offer us.

Guilt can guide us when we get off track, but guilt is more like bumpers on bowling lanes, not a beacon to follow through a storm.

And I decided that the guilt I felt today is just the voice of an old rulebook I never agreed to.

One I don’t have to follow anymore.

The real question—the one I’m finally beginning to ask—is not what should I have done differently?

Instead, today I ask: what kind of man do I want to be now?

We outgrow many things in this life. Uniforms, like identities and roles we play, have their seasons. They serve their purpose, and then they live on in memory. They are not meant to last forever. They are meant to be shed.

Grief and guilt may have stayed with me longer than they needed to. They had their season, too, just like the uniforms.

But I’m ready to hang them up now.

About the Author

Hi, I’m Eric. I’m a scientist, former aviator, homeschooling dad. I used to chase titles and prestige. Now I'm just trying to understand myself and help others, one story at a time.

If this essay spoke to you, please consider sharing it.

I wrote it for you, and others like you.

I was reminded of a quote from The Stalker (Andrei Tarkovsky):

“My conscience wants vegetarianism to win over the world. And my subconscious is yearning for a piece of juicy meat. But what do I want?”

I find the hardest thing to do is dwell in uneasy stillness. It’s wonderful to watch you reckon quietly with the contradictions between all your selves: past, present, and future.