I arrived yesterday at a location I hadn’t seen in twenty years: Navy boot camp, officially known as Navy Recruit Training Command. I am here collecting data for a research project I lead. This will be my last data collection trip as a uniformed scientist, another “last” in a string of “lasts” as I hurl towards my impending retirement.

The sky was ominously gray, the rain falling in sheets. Forty-five degrees and windy—classic, miserable Chicago weather. I met my colleagues in a nearby parking lot, where we crammed ourselves into one vehicle: a clown car full of scientists and computers, with an officer in uniform—me—behind the wheel.

Driving across the base felt like stepping into a time warp. Rows of sailors marched in formation with seabags on their backs, shouting cadences at full volume, somehow managing to look both motivated and miserable.

We pulled up to the barracks and began unloading. Crossing the quarterdeck was like stepping straight into memory.

The barracks were exactly as I remembered them.

White cinder block walls stretched down long, windowless corridors, broken only by the occasional fire extinguisher or faded motivational poster. Frosted glass let in a pale, diffused light—but not enough to tell the time of day, and certainly not enough to catch a glimpse of the sky. The outside world feels distant here, like something imagined.

Inside the squad bays—known as “compartments” in Navy speak—hundreds of identical steel bunk beds are arranged in precise rows. Blue blankets folded tightly. Boots lined up beneath each rack. Everything is uniform. Everything echoed. The sharp tang of Simple Green clung to the air, mingling with the musk of unwashed uniforms and too many bodies packed into shared space.

Shouts traveled easily down the tiled hallways—someone calling a name, someone else barking orders.

Walking through these buildings brought back a weird mix of nostalgia… and maybe some mild trauma. :)

The walls were the same. The smell was the same. The shouts were definitely the same. The only real difference? The recruits.

They’re the age of my kids now.

Which is probably why everything felt a lot smaller than I remember.

The population I’m collecting data from consists of sailors who have completed basic training—but are now stuck in a holding pattern. Several hundred young men and women, all waiting for permission to move forward in their military careers.

Some are here waiting for their security clearances to come through. Others are recovering from injuries, waiting on medical to clear them.

But they all share one thing in common: they’re ready. Restless. Eager to get on with it.

In the meantime, they live in a sort of in-between state—not quite in boot camp, but not quite free either. They still sleep on bunk beds in open squad bays, 50-60 to a room. They still share common restrooms and showers—privacy is non-existent. They still eat at the chow hall. They aren’t allowed to wander. They aren’t allowed to be in civilian clothes. It feels sort of like a minimum-security prison, filled with people on crutches and stories to tell.

My sponsor for this trip is a Recruit Division Commander (RDC)—what the other services call “drill instructors.” They are instantly recognizable. The gravelly voice, raw from constant yelling. The way they carry themselves. They move with the force of alpine snowplows—powerful, unyielding, determined to push through anything in their way. A red braided cord loops around the left shoulder of whatever uniform they’re wearing, marking them as “red ropes.”

Seeing those red ropes again triggered something primal—an old, instinctive fear. As a recruit, RDCs hold absolute power over you: when you can eat, when you can sleep, even when you can use the restroom. If you screw up, the best-case scenario is their hot breath in your face at full volume. Worst case? Push-ups or 8-count body builders (burpees) until your limbs give out or you puke up lunch.

When I came through boot camp, there were only a few integrated divisions with both males and females. They slept in separate compartments but did everything else together—marching, training, inspections. My division was male-only, so the only RDCs I interacted with were men—with one memorable exception.

Hercules Revisited

One evening, midway through training, a few of us decided to goof off while the rest of the division was busy cleaning. We were all gunning for special operations programs—an especially motivated group that saw every spare moment as a chance to push ourselves. That night, we each took turns attempting an absurd physical feat: holding our bodies at a 90-degree angle on the edge of our racks. It’s a move that requires serious core and upper body strength—part circus stunt, part ego test.

When it was my turn, I kicked up my feet and locked my arms against the vertical steel bars of the bunk bed, holding myself rigid and horizontal like a flag in the wind.

That’s when she walked in.

More like she charged in. A female RDC, built like a linebacker and radiating pure fury. It felt like she’d been waiting for this exact moment.

Hey, Hercules! she barked, arms swinging wildly as her massive stomps closed the distance between us in seconds.

We all snapped to attention.

Is there a single brain cell in that head of yours that thought this was a good idea, recruit?

No, petty officer! I shouted, immediately kicking myself for playing into her game.

Well, that’s too bad, Hercules. Seems you like attention. So let me help you get some!

She turned to the compartment. GATHER UP, EVERYONE! she barked. My heart sank.

The entire division circled around me.

Seaman Recruit Vorm is gonna show us how much of a badass he is.

I was ordered to recite the 11 General Orders of a Sentry—while doing pushups. Ten pushups per order. My division watched with thinly veiled amusement. A few smirked. No one dared laugh out loud. They all knew better. One wrong sound and they’d be down there with me.

Nice job, Hercules, she said once I’d finished. I stood at attention, panting.

You had enough? she asked.

And here’s where I made another mistake.

No, petty officer! I shouted, thinking it would make me look tough.

In retrospect, all it did was confirm I was dumb.

Very well, she said, smiling.

Then she turned to the rest of the room. On your feet, all of you!

Now everyone had to join me.

Pushups and general orders. Ten for each.

Suddenly, the smirks vanished. In their place were the kind of looks that promised quiet retribution. Maybe an ‘accidental’ slip in the shower. Maybe something worse.

When we finished, she dismissed the group and told them to resume cleaning before lights out.

She approached me, her arms crossed. My body was shaking from exhaustion, sweat dripped from my face down my nose.

Vorm, she said. Is that German?

No, Petty Officer, I replied, still catching my breath. It’s Dutch. But I do have some German ancestry—

Shut up, she cut in, voice suddenly calm.

I didn’t ask for your genealogical record. Learn how to keep your mouth shut.

And with that, she turned and stomped out of the compartment—boots thudding, door swinging shut behind her.

You sure got a way with the women, my bunkmate muttered in a deep southern drawl.

Thanks, by the way, he added, rubbing his now sore shoulders.

Now, walking through the passageways with my red rope sponsor at my side, I felt the shift in power—and I was grateful to be on this side of boot camp. No longer the one being shaped by the system, but someone who has come through it, intact.

Maybe even a little wiser.

Coming Back to the Beginning

My team and I wheeled in our gear and began setting up—laptops, extension cords, spare batteries, consent forms. The same institutional tables. The same off-white walls. The same smell of industrial floor cleaner, old rubber, and recycled air. The only difference now is that I carry a badge instead of a sea bag.

In the room next door, my sponsor called the entire division to attention. I heard the shuffle of boots and the echo of authority in his voice. I stepped into the compartment.

More than a hundred sailors stood in tight formation—rows of ten across, backs straight, hands clasped behind them at parade rest.

Attention on deck! my sponsor shouted.

The room snapped into perfect silence as they came to attention in unison.

Good morning, I said.

GOOD MORNING, SIR! they responded, loud and immediate.

And just like that, I was back in it. Not as a recruit, but as an officer. But not just any officer—a scientist. A guest. Someone who still remembers what it felt like to be on the receiving end of all this.

I introduced myself and explained the purpose of the study. Why it mattered. How their participation helped. I told them I could take a maximum of 36 volunteers—three sessions of 12.

Only four people declined.

With the recruiting complete, I moved back down the passage way towards the room designated for our research team.

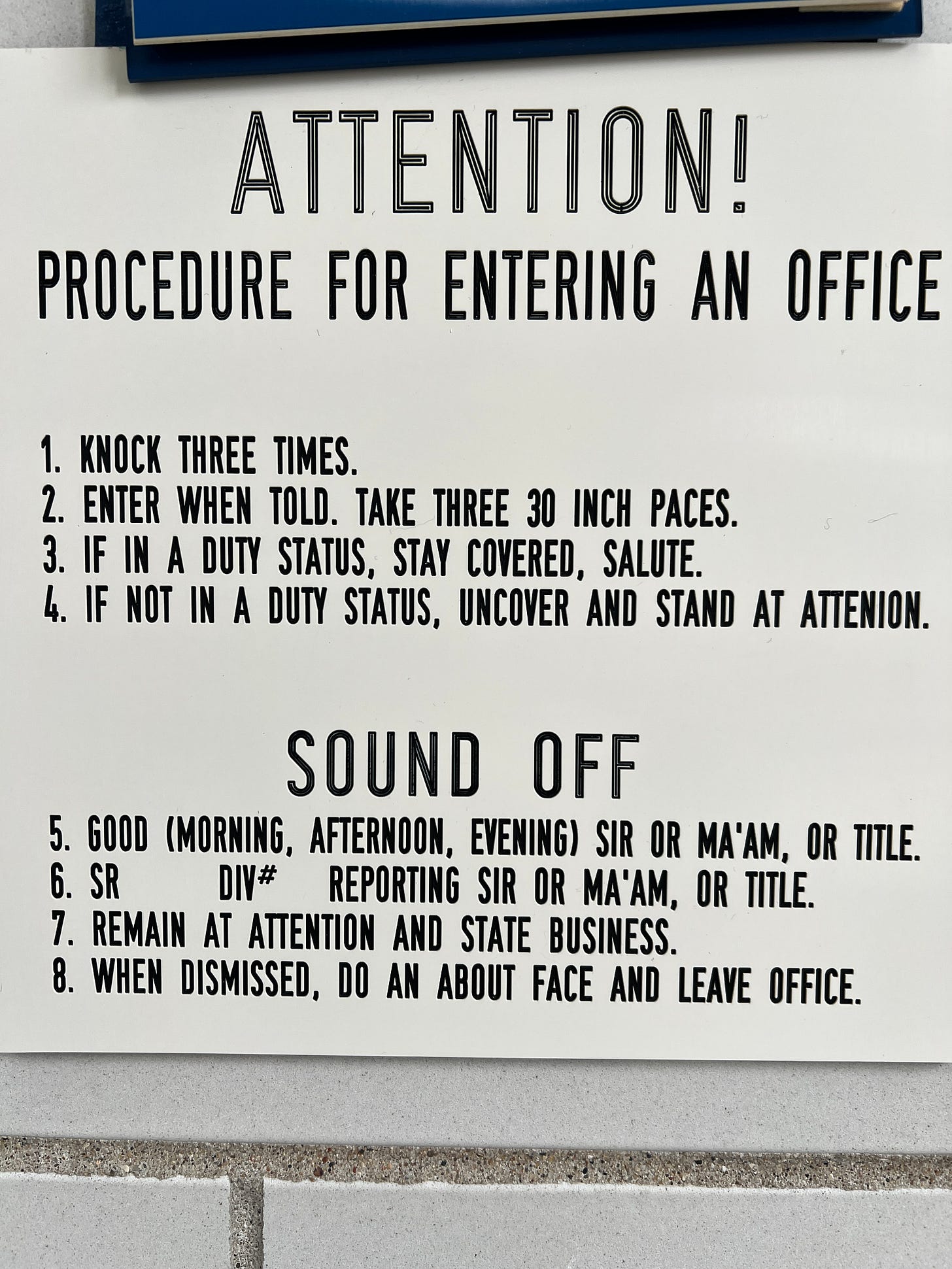

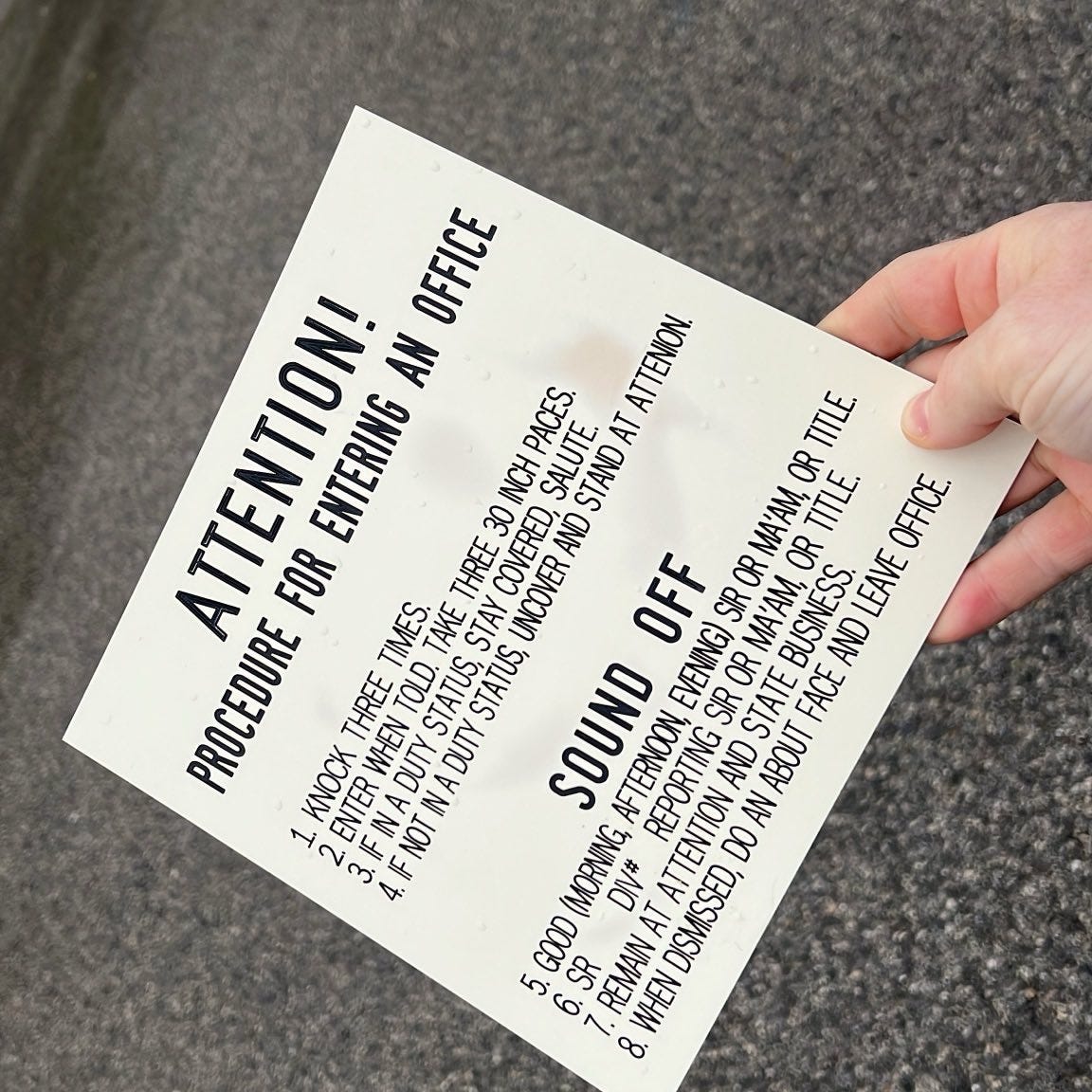

Along the way I spotted a placard on the wall—the exact kind that hung here twenty years ago when I came through as a recruit. It listed instructions for how to enter an office properly: knock once, stand at attention, announce yourself clearly, wait for permission. A recipe for how to avoid getting yelled at.

What recruits don’t realize is that the game is rigged. They’ll get yelled at no matter what.

Still, seeing that placard gave me an idea.

It would be really great to have one of those as a souvenir, I thought.

And just like that, a plan began to take shape. I didn’t know how exactly I’d make it happen—but once I get an idea in my head, I tend to let my subconscious work out the details while I go about my business.

I had two more days of interactions ahead—plenty of time to let my charm do its thing.

A Fireball in Khakis

While supervising data collection, I heard a commotion in the hallway. I stepped out to witness an amazing sight: a female RDC—a Navy Chief—with a square jaw, a tight bun of dirty blonde hair, and fierce blue eyes that looked like they could freeze saltwater. She was part lumberjack, part Viking—and I wouldn’t have been surprised to learn she played either role on the weekends. Maybe both. At the same time.

She stood toe-to-toe with another sailor in the hallway—a huge guy, easily 6’4”, built like a refrigerator with arms. Didn’t matter. She barked like a pit bull and moved like one too—snapping, circling, eyes locked. Her words cut through the air like an oxygen torch, precise and merciless.

Oh, you think you’re special ‘cause you got shoulders? I’ll break you down to your bone marrow, sweetheart!

You better unf#% yourself before I do it for you!

That face you’re making—wipe it off before I use it to mop this deck!

I said move like you got a purpose, not like you’re lost at a county fair!

You’re not a tree, sailor—stop standing there like you’re waiting to be watered!

The poor guy stood there frozen, visibly rattled, as if he’d just been hit by a verbal flash bang. The hallway cleared out fast. A couple of passing recruits dashed into another room as if to yell “duck and cover!”

She wrapped up her verbal demolition, spun on her heels, and spotted me standing nearby.

How you doing, sir? she asked, smacking her gum and giving me a half smile.

I nodded with raised eyebrows, half-intimidated, half-impressed.

I’d just watched a human fireball tear down a fully grown man with surgical precision.

I will not get in this woman’s way, I pledged to myself.

The absurdity of it all lingered for a while. That much energy, that much authority, packed into such a compact, gum-snapping package. It was almost enough to make me forget why I was here in the first place.

But between sessions—while participants dutifully clicked through computer tasks and filled out surveys—I found pockets of quiet. Enough space to catch my breath. Enough stillness to read.

I opened Substack.

Standing Up or Standing Out

I have a few favorite authors whose work feels like conversation rather than performance. But that morning, everything I read blurred together. Same tone. Same arc. Same themes.

Wow… who knew there were so many people trying to recover from trauma and live authentic lives?

Maybe it was the algorithm. Maybe it was something deeper. Either way, a flicker of unease crept in.

How do I stand out in a sea of voices saying what I want to say?

I’ve learned something about that feeling over the years. When I begin to feel insignificant, I often try too hard to stand out. I end up straining—too loud, too eager, too performative. The intellectual equivalent of jumping up and down in front of the classroom, waving my hand just a little too high. Trying to be chosen. Trying to be noticed.

The end result is predictable to me now: I get off balance. I lose my center. I lose my sense of self. I become whatever version of me I think you want me to be, and pretty quickly I forget who I really am.

I see that same desperation to be seen in some of the sailors who linger after data collection. They tell me things quickly, urgently, trying to pack as much identity as they can into a brief interaction. Some recite accomplishments. Others mention hardships.

None of it sounds untrue—it just feels effortful, like the energy behind it is bigger than the story itself.

They’re not lying. They’re trying.

Trying to be seen. Trying to be someone, in a place designed to make them feel like no one in particular.

I understand. I’ve lived that tension.

When I began my career as a scientist, I often felt inadequate. My advisor’s CV was 54 pages long. He chaired scientific panels at the FAA and NASA. He wrote the textbook I studied—the same one most major universities used to teach human-computer interaction.

I had none of that. No titles. No prestige. No publications.

All I had were ideas.

But when I stopped trying to impress and started simply articulating what I believed—clearly, thoughtfully—people listened. Slowly but surely, I was invited to speak at universities. Then I was invited back. I became a mentor in formal programs for young scholars. I sat on conference panels. Eventually, I was asked to collaborate on writing books.

Not because I forced my way in.

But because I offered something real.

Some mornings I still feel that tug—that fear that my voice might disappear in the noise. I worry no one will read what I write. That no one will care.

But I remind myself: I’m not here for competition.

I’m here for connection.

My job isn’t to shout louder. My job is to speak clearly, from the life only I have lived.

I’m not trying to be louder than the rest. I’m just trying to speak with fidelity—to tell the truth of my experience in a voice that sounds like mine.

Not to be seen.

But to be known.

Because today, when all the noise dies down, that’s what matters most to me.

Mission Accomplished

The next two days passed quickly—familiar rhythms of data collection, quiet conversations between sessions, the occasional joke exchanged with a sailor who needed to be seen. We wrapped up our final round, packed the gear, shook hands, and said our thanks.

Outside, the sky had turned the color of dull steel. Rain tapped against the frosted windows, carried sideways by a biting wind. The barracks, always echoing with noise, seemed briefly still.

As I was wheeling out the last of our gear and preparing to leave, I spotted the placard on the wall again—the same one that had caught my eye on day one. I remembered my goal.

The female RDC—the Viking lumberjack in Navy khakis—was sitting at a computer in a nearby office, typing with the same intensity she brought to yelling.

I approached, hesitated for a moment, then knocked—three times, of course.

Hey, Chief, I have a strange request.

Hit me, she said, not even glancing up from her screen.

Is there any chance you have an extra one of these placards lying around? Maybe in a storeroom somewhere?

She paused and looked at me a moment, chewing her gum. Then, she stood and walked toward the doorway. I instinctively took a step back.

Arms crossed, lips pursed, brow furrowed—she looked me up and down like she was assessing a dented piece of equipment. Then, without a word, she stepped past me.

She turned to the wall of her office, stared at the placard for a beat, and then—without ceremony or hesitation—began to rip it off the wall with her bare hands.

Not unfasten. Not remove.

She ripped it from the wall.

With a surprised look on my face, I glanced up and down the corridor, suddenly aware of how this might look. I hadn’t told her to rip it off the wall—but as the senior officer in the building, it wouldn’t take much for someone to assume I had.

My eyes flicked to the nearest security camera. I imagined the playback later: Chief tearing state-sponsored signage from government property while I stood by like a satisfied art thief.

Uh… Chief? I said, hesitantly.

The placard was stuck to the wall with what had to be industrial-strength 3M adhesive. She worked at it with her fingers for a full minute, trying not to snap it in half.

Maybe you need a putty knife or something? I offered, cautiously.

Nah, sir, she grunted, still prying. Saying I need a putty knife is like saying I need a man.

With one final grunt, she tore the placard from the wall and turned toward me. Without a word, she slapped it against my chest.

And clearly that isn’t the case.

I stood there a moment, eyebrows raised. I swallowed.

Thank you, Chief, I said, a smile spreading across my face.

Welcome, sir, she replied with a wink. Then she returned to her office—like a dragon returning to its lair.

I paused in the corridor, letting my eyes drift over the space one last time. The same white cinder block walls. The same smell of floor cleaner and sweat. The same boot steps echoing down the hall.

Twenty years have passed. A lot has changed.

Still got a way with the women, I thought to myself as I stepped out into the cold rain, the placard in my hand.

Some things never change.

About the Author

ES Vorm, PhD is a soon-to-be-retired Navy scientist who is still learning how to keep his mouth shut. He writes about identity, memory, transition, and what it means to live with integrity on both sides of the uniform. You can find more of his work at The Recovering, where he documents the journey from survival mode to something like peace.