Summary

For twenty years in the US Navy, I chased—achievement, approval, perfection. It took me far, but it also left me burned out, anxious, and lost in my own head. This essay reflects on the final Navy fitness test of my career, and how, for the first time, I ran without chasing. Steady, clear, and free.

Twenty years ago last week, I enlisted in the United States Navy.

I was 25 years old—married for four years, no kids. I had graduated from college the year before and learned the hard way that a bachelor’s degree in psychology is about as useful on the job market as a screen door on a submarine.

After nearly a year of searching, the only jobs I could find were minimum wage roles I could’ve done without taking on $30k in student debt. Turns out, the degree was also as meaningless to the Navy as it was to any other employer. When I slid my diploma across the recruiter’s desk and asked about a commission, he looked up politely, pushed back from his chair, tented his fingers and said,

Well, son. That there piece of paper is what we call decorative—kinda like them towels your mama puts out for guests. They look nice, but don’t nobody actually use ’em.

What else can you do? he asked, drumming his fingers impatiently.

I quickly ran down my very short list of qualifications. Aside from my decorative degree, I had the following accomplishments to my name:

• I had been a piano performance major at a top music school in the Northeast, but I never finished—each year’s tuition could’ve bought me a baby grand piano made of solid gold. At least that would’ve held its value.

• I had written a collection of poems, a few of which made it into the local newspaper—mostly because the editor owed my mom a favor. One even won an award at the county fair, which means I probably peaked artistically somewhere between a haiku about cows and a wood-carved rooster.

• I had a solid little collection of portraits—friends posing under lights I barely knew how to use, shot on university gear I definitely wasn’t cleared to check out, printed in the darkroom on paper I didn’t pay for. But when one of my headshots helped a friend win a few beauty pageants, I gained minor celebrity status—at least within a 100-foot radius of the vending machines in the student union, which I designated “my gallery” by hanging up my work with thumbtacks and masking tape.

These were the skills I had—scattered musings from a talented but aimless wanderer, trying to chart a course by chasing butterflies and calling it a map.

Oh! I said, grabbing at my wallet and suddenly remembering something very important. I also have these.

I pulled out my stack of emergency medicine certifications—Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) Instructor, Prehospital Trauma Life Support (PHTLS) Instructor, Basic Cardiac Dysrhythmia Instructor, Emergency Vehicle Operator. It looked impressive on paper. In reality, I’d spent most of college working in emergency rooms and riding boxes—ambulances—hauling old ladies out of showers and scooping up asthmatic kids from food courts. Not exactly ER, but it paid the bills.

My recruiter’s eyes widened.

Son, he said as his face brightened into a smile, revealing a smile full of white teeth—and one gold one that caught the sun.

I can have you a paycheck in two weeks!

It was no surprise he saw value in what I laid in front of him. Unlike my extensive knowledge of psychobabble—which, if I’m honest, was mostly a thin disguise for self-therapy—my experience in emergency medicine was both practical and timely. By the time I stood before the recruiter in April of 2005, the U.S. was deep into the Iraq War, with operations expanding under the broader banner of the “War on Terror.” Combat medics were in high demand, and I had the kind of hands-on experience that made me an easy fit—and an even easier box to check on the recruiter’s monthly quota sheet.

True to his word, two weeks later I stepped off a bus at midnight into a wall of screaming drill instructors who circled like hyenas, ready to pounce. Bleary-eyed and dry-mouthed, I snapped to attention on a set of yellow footprints painted on the concrete and asked myself the same question everyone who’s been through that moment has surely asked:

What the hell have I done?

Where the Time Has Gone

I can’t say twenty years in the military flew by—more like getting stuck in a book club with a really long book. There were moments I couldn’t put it down, and others where I seriously considered faking my own death to get out of it. But I’d come too far to stop. I guess that’s what the sunk-cost fallacy looks like in a uniform.

The truth is, it wasn’t all bad—or all good. I traveled the world. I saved lives. I did things most people only read about in recruiting posters and thrillers. I stood shoulder-to-shoulder with some of the most capable, courageous professionals this country has ever produced. I wore the uniform with pride and earned distinction among my peers.

And yet, behind the medals and memories, I also learned how to mask pain, absorb mistreatment, and push myself to the brink. I burned out. I drank too much. I developed a level of anxiety I wouldn’t wish on anyone, and thanks to some nasty head trauma, I now lose my train of thought more often than I lose my keys. Serving gave me everything—and it took a lot, too. That’s the truth no one prints on the brochure.

One Of Many Lasts

These days, as my retirement date nears, I have experienced a series of “lasts.”

I already had my last flight years ago, thanks to a variety of medical issues that rendered me too much of a risk in the flight environment.

A few weeks ago I completed my last online training for cybersecurity—an hours-long click-through scenario that tested my patience, mouse-clicking stamina, and ability to pretend I hadn’t already guessed the “correct” phishing email six slides ago. By the end, I wasn’t sure if I’d secured the network or just aged five years.

This morning marked another “last.” It was the final time I had to complete the Navy’s physical readiness test—a biannual ritual designed to ensure all service members meet baseline standards of physical fitness. The test includes two minutes of push-ups, a forearm plank held for as long as possible, and a cardio event of your choice: elliptical, stationary bike, lap swim, or my personal preference—running a mile and a half.

I’m not a physically imposing man. In fact, I’m downright diminutive—several standard deviations below the average height for American males. But I’ve always had a natural ability when it comes to physical fitness. I could swim like a fish. I could crank out pull-ups for days. I could hike for miles without complaint.

My fitness scores were always excellent, but never perfect. The Navy’s test allows for 100 points per event. I’ve consistently maxed out push-ups and planks (or sit-ups, back before the shift to planks). But my short legs were never built for speed. For me, sprinting looks and feels a bit like trying to win a drag race on a tricycle. I’ve always preferred long-distance running for this reason. A 1.5-mile run barely counts as a warm-up for me—but despite years of grueling training running marathons and triathlons, I never earned the coveted 300-point perfect score on the Navy’s fitness test because of the run.

So a month ago, when I signed up for what would be my last official Navy run, I set a quiet goal for myself: go out on top.

I wanted to run faster today than I had at any point in my 20-year career.

Not exactly ideal timing, considering I’d just spent the previous three weeks traversing Asia with my 13-year-old daughter and had only run twice—once to breakfast, and once to catch a bus… which we missed.

The Last Run

I arrived at the base athletic center this morning and was greeted by the familiar sights and smells of a military gym—sweat mixed with disinfectant spray, the sharp clinks and clanks of iron plates rising and falling. I stood among a group of strangers, all there for the same purpose, and quietly prepared for what would be my final round of push-ups and planks.

The maximum push-up requirement had dropped with age—from 84 when I first joined to 68 today. Back in boot camp, I made it my mission to hit all 84 in under 70 seconds, and I did. Today, I set a new goal: 68 in 50 seconds—and I did that too. As for the plank, I regularly hold five minutes in training, so the Navy’s maximum time of three minutes and fifteen seconds passed easily.

“Not bad for an old man,” I half-joked as I rose from the mat and headed outside toward the track—my hips, knees, and back providing a percussive soundtrack of pops and clicks that sounded like someone trying to open a bag of chips in church.

I stretched beneath the soft warmth of a spring sun, surrounded by the scent of honeysuckle and freshly cut grass. A light, 65-degree breeze cooled the sweat on my skin and filled my lungs with a calming grace that made me grateful for a job that requires me to exercise outdoors.

The group of us—about twenty in all—gathered at the starting line of a gravel track, each preparing in our own way. Some wore earbuds and blasted high-energy music. Others stretched quietly off to the side. I passed the time with small talk, cracking a joke about my PT shirt—the only one still wearing the infamous generation-one version, made from fire-resistant material. It weighs a ton and doesn’t breathe at all, but hey—if I burst into flames during this run, I’ll be safe for at least twenty seconds!

I looked at the faces around me—smooth-skinned, full of energy, some still carrying that wide-eyed optimism that comes with being new. One young man had just arrived a few weeks earlier. This was his first official Navy physical readiness test. I caught a glimpse of myself reflected in another’s sunglasses—the grey at my temples, the fine lines at the corners of my eyes. I’ve lived a lot in the past twenty years. My body may only be 45, but some mornings it feels like it’s already drawing a pension.

But it wasn’t my appearance that marked the biggest difference from the man I was twenty years ago. It was the mindset. The quiet acceptance. This morning I had a calm that came not from certainty, but from trust. I retire in six months. What happens after that? I honestly don’t know. And strangely, that’s okay. I started this journey as an E-1, fresh from a recruiter’s office with a decorative degree and a head full of questions. I’m leaving as a mustang officer two-thirds up the food chain with twenty years behind me, a wall full of plaques, and a soul that’s carried both laughter and pain. All I needed to know this morning was that I had a run to do, and that’s all I thought about on the lonely 1.5-hour pre-dawn commute.

Years ago, I would’ve been fine-tuning a five-year plan by sunrise, complete with contingencies and risk assessments. Today, I was just glad my socks matched—and that I hadn’t accidentally grabbed my lawn-mowing sneakers. It’s not apathy. It’s clarity. I care—but more about what matters, and less about what I think you think matters.

And so, when it was time to run, I found my lane, calmed my mind, settled into my breath, and eased into my stride. The cool morning air met the warmth of the sun, creating that perfect contrast against my skin. The grey gravel crunched beneath my feet, kicking up a soft haze of dust with each step. The smell of freshly mown grass mixed with the sharp tang of sweat in the air. Around me, the quiet sounds of exertion—rhythmic footfalls, labored breathing, the occasional grunt—formed a kind of chorus. Bodies moved in and out of sync, each person locked into their own effort, their own internal pacing.

One by one, I passed other runners, moving around them with comfortable strides. Once upon a time I would make it my goal to lap at least one person—a sign of dominance, a badge of honor pinned on my ego’s chest. But I didn’t think about anyone else running today. My mind was calm. My breathing stayed even. My legs moved with practiced ease. I knew this rhythm. I knew this body. I knew this moment.

That’s the gift of experience, isn’t it? The quiet confidence that comes not from hoping you can do something—but from knowing you already have. Time and time again.

More than anything during my last official Navy run, this morning I felt grateful.

Grateful to be free of the relentless need to prove myself.

Grateful to be free of the anxiety that once accompanied every run, every test—the fear that I wouldn’t make the cut.

Grateful to be free of the shame that came from falling short of impossible expectations I had set for myself, the voice in my head that whispered you’re not good enough, you’re falling behind, they’re going to find out you don’t belong.

For years, I had run under the weight of those thoughts—chasing perfection, terrified of failure, convinced that if I didn’t perform flawlessly, I’d be dropped from special programs or quietly exposed as a fraud. That’s the part no one tells you: the hardest miles are the ones you run in your own mind.

When I was younger, I probably spent at least half my energy and time worrying in my head. I could literally spend DAYS worrying about what you thought of me, thinking how to influence your opinion of me, plotting ways to earn your approval. It is a wonder I had any energy to actually do anything but worry about what you thought of me back then.

But not today.

I don’t need anyone to tell me I’ve done enough. I know I have. That is two parts experience and one part knowing I have put in the work. I think at some point I just learned the fundamental lesson behind the tortoise and the hare, and having adapted the tortoise’s steady routine, life is easier in virtually every way.

And so I was genuinely surprised when I found myself at the head of the pack, leading a group of twenty-year-olds whose birthdays closely aligned with my pay entry base date. I didn’t try to beat anyone. But I ran with the determination to meet the goal I had set for myself, knowing that any goal I set under those conditions will be met so long as I put in the two necessary ingredients: attitude and effort.

Ten minutes and thirty seconds later, I crossed the finish line first in the group—clocking my best run time in twenty years.

My total score came to 290 out of 300, the highest I’ve ever recorded on a Navy physical fitness test.

No one cheered. There was no certificate. Just a quiet moment of completion. A private sense of closure. The kind you earn, not the kind you’re given.

I turned around and stood by the finish line to cheer on the others, giving high fives to strangers as they came across, panting, gasping—one of them vomiting.

No, I didn’t reach the mythical 300. But I came damn close. And more importantly, I finished strong—not just in numbers, but in spirit.

And even though I’ve probably finished half a dozen posts with these same words—today, that was enough.

About the Author

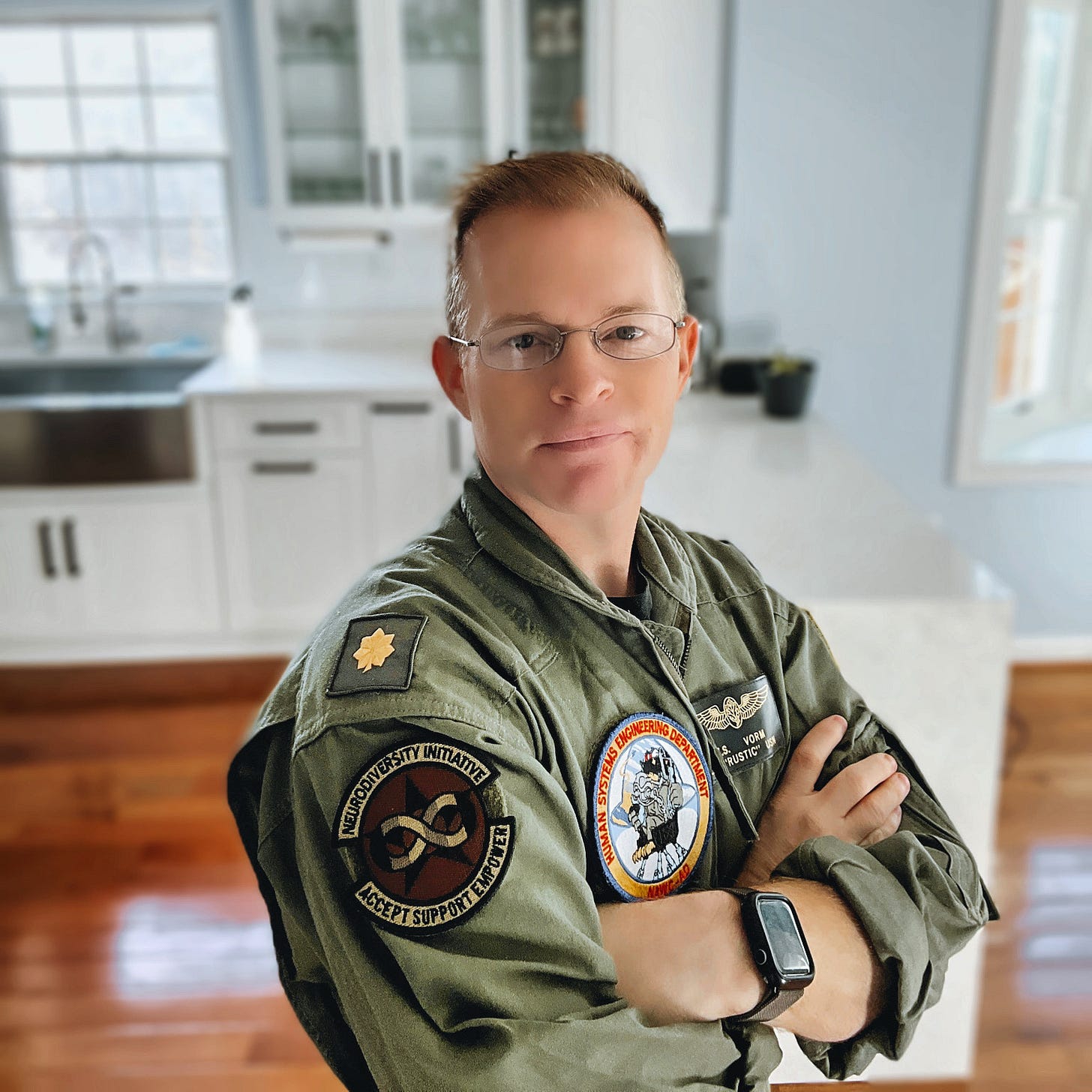

ES Vorm, PhD is a retiring Naval officer, combat veteran, and recovering overachiever. After two decades of military service as a Navy Corpsman in special operations, aviator, and defense scientist—he’s trading missions for mindfulness and burnout for balance. He now writes about recovery, identity, and what it means to live well after letting go of the chase.

This is everything