Models of Relationship

When mental maps don’t match, people crash too.

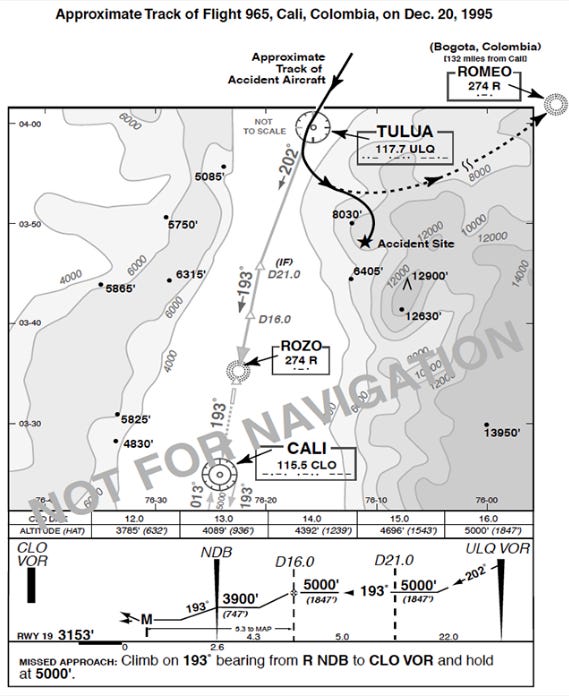

On December 20, 1995, a passenger airliner was descending into Cali, Colombia, just in time for Christmas. Using the autopilot computer, the pilots selected what they believed was the next waypoint on the way to the airport—“Rozo.” Using the interface, they selected “R,” assuming that should stand for “Rozo.”

But the autopilot had other ideas. It selected “Romeo,” a completely different waypoint located far behind them, instead.

The autopilot did this because it was programmed to hit every waypoint in the list in order, and Romeo had never been ticked off the list because the pilots had flown around it earlier in the flight.

The pilots assumed the autopilot would select the next waypoint in the sequence towards the airport. They never imagined the computer would ever look backwards, let alone turn the airplane around to hit a waypoint they already passed.

But that’s exactly what the autopilot did.

Not because it was faulty. Because this is how the autopilot was designed—to hit every waypoint in a list.

So, with Romeo selected as the next waypoint instead of Rozo, the airplane initiated a 180-degree turn back toward an earlier waypoint.

Normally this would be a minor inconvenience; something the pilots would quickly recognize and fix.

But this was no minor inconvenience.

That’s because an autopilot system does not know anything about the terrain around an aircraft. It doesn’t have eyes. It can’t look out the windows. It only knows how to put the airplane at a certain heading and altitude.

So when the autopilot began to turn the aircraft, it had no idea it was flying next to a massive mountain.

When the pilots felt the aircraft turning to the left, they became curious and started looking at the computer to figure out what was happening. Unaware of the danger and unable to see terrain in the dark, the pilots assumed all was well as they tried to understand why the aircraft was turning around. Moments later, the jet slammed into a mountain ridge.

159 people died.

The autopilot didn’t fail, nor did the pilots.

The source of the error was a misunderstanding of how the system was designed to work.

Flight schools today still teach this as a textbook case of mental model mismatch.

What is a Mental Model?

A mental model is the internal map we use to navigate the world. It is the sum of assumptions, expectations, and beliefs we carry about how things work. It’s the story we tell ourselves about what comes next. It is what we think a word means, or even what someone else is thinking when they speak to us.

We all operate from mental models, but they play the largest role when working with others.

For example, if you and I decide to build a deck, we need to have a shared mental model to successfully work together. What we are there to do, in what sequence, and the division of labor are all things we must agree on if we are to work as a team.

We update our mental models through communication. Every question asked, every clarification offered, every moment spent confirming we’re on the same page is how we align our maps. Without that constant exchange, we’re left assuming the other person sees what we see and knows what we know.

And that’s where things start to break down.

A classic and simple example of mental model mismatch in teamwork is if one person thinks “let’s meet at eight” means 8 a.m., the other assumes evening.

But model mismatches in relationships are often much more complicated than simple miscommunications.

Two Maps of Friendship

By 2010, I was done.

Done with deployments. Done with the global war on terror. Done with the version of duty that demanded everything and offered little in return. I had climbed the ladder, earned the stripes, followed the path—and felt emptier with each step. I was disillusioned with a system that asked everything of me, and consistently failed to deliver on its promises.

There was one good thing about that time in my life. I had a good friend named Chuck.

We’d met a few years earlier and had become close—gym buddies, hiking partners, fellow photography enthusiasts. His kid and mine were born close to each other, so we often talked about the joys of parenting a toddler. Chuck was a beast in special operations—the youngest to achieve team leader at 2nd Reconnaissance Battalion in recent history. He had the respect of everyone around him, and I looked up to him. In a world where so much felt uncertain, his friendship felt solid. When everything else in the Marine Corps felt broken, our friendship was one of the few things that still made sense.

That spring, I was offered a prestigious teaching post at a special operations school—one that would have fast-tracked me to the next rank. But I knew what it would cost. The post involved a lot of time away from home. It would be like another deployment, even though this duty was supposed to be my ‘break’ in between deployments. I had already set my sights on using my next three years on active duty to go back to graduate school and earn a masters degree at night. I knew the job I was being offered would never give me the time I needed to achieve that goal.

What looked like a golden opportunity for my immediate career began to feel like a poisoned apple for my long term life.

One day, as I was wrestling with my decision of whether or not to take the job, I vented on Facebook. I said something like: I wish I could serve in ways that fit who I am, instead of always having to fit myself into systems that don’t seem to fit.

A few hours later, I saw that Chuck had replied to my post. He wrote:

Maybe you should be grateful for what you have and stop embarrassing yourself. Or maybe you should just exit stage left.

His words hit like a punch to the gut. I couldn’t understand how he could be so callous and uncaring. I felt like he didn’t understand me at all. What he said left me bewildered and hurting.

I wanted to touch base and clear the air, so I called him the next day, hoping to talk. He was cold. Dismissive. Our conversation lasted only a few minutes. I couldn’t understand how he had gone from working out in the gym, going on hikes and photo trips together, to suddenly being so callous and distant.

Self-doubt has always been a common response when I find myself in conflict with others, so the next day, I read the post again to see if I really had been unreasonable in my expectations. What I saw instead shocked me even more.

Chuck had unfriended and blocked me on Facebook.

Just like that, he was gone.

For days I felt like I’d been kicked in the chest. I couldn’t make sense of it. This was someone I’d trusted—someone who had shared workouts, meals in my house, toddler milestones. And now? Nothing. No explanation. No closure.

I never heard from him again.

I replayed everything. Was I too vulnerable? Too honest? Had I crossed some invisible line?

The only conclusion I could come to was devastating: I had failed as a friend.

When I went to graduate school and began learning about the dynamics of healthy relationships, I began to understand that experience with Chuck differently.

To me, a friend is someone who rallies to you when you’re confused, hurting or in doubt. A friend is someone who shows up when you’re questioning everything—especially then!

Listening. Holding space for doubt. Standing by someone even when they’re not at their best. That is what I do for friends when they are struggling. Even if I personally disagree with someone’s decisions, I chiefly see my role as being a listener and a supporter to help them on their journey. That is my model of friendship.

Chuck’s model of friendship was evidently very different. He lived life according to a kind of hierarchy of loyalties. At the top was the Marine Corps. In his world—especially in special operations—questioning was dangerous. Thinking was dangerous. Doubt wasn’t something you comforted; it was something you cut off before it spread. For him, allegiance to the cause came first. Everything else, including friendship, came second.

And when I reviewed that conflict through the lens of models of relationship, I could easily see that although we got along great doing superficial things like hiking and taking photos, it was clear that we could never really be close friends because our models just didn’t match. It was only a matter of time before those differences became apparent.

The more I looked at his behavior and tried to understand his model, the more I saw a fundamental mismatch that not only took the sting out of how it ended, but also showed me he really wasn’t a person I would actually want to include in my life.

Because I want friends who care more about me than organizations.

I want friends I know will be there when I struggle, not who will abandon me when I speak my mind.

When Models Don’t Match

When people operate from different models of what it means to be a friend, a partner, a parent, or a teammate, the result is often confusion, hurt, and sometimes loss. Not because the other person is flawed—but because their maps don’t align with ours.

For example, maybe he won’t turn up the heat, even when you’re shivering—not because he’s an insensitive jerk, but because he sees his role as the provider, and providing means saving money. In his model, frugality and efficiency are more important than ease. His focus is on the bottom line, not on your comfort.

Maybe she doesn’t reach out when you’re hurting—not because she doesn’t care, but because she believes real respect means giving people space. Her model respects the individual, and she sees relationships as two independent people agreeing to work together, rather than two people becoming one unit.

Maybe your friend gets upset when you make a big life decision without telling them—not because they’re controlling, but because their model of closeness means being included in those conversations. To them, intimacy isn’t just about sharing feelings—it’s about thinking out loud together, processing choices side by side, before the decision is ever made.

Why This Matters

Examining models of relationship helps us in a variety of ways.

Firstly, it means we can stop taking everything so personally. We can stop assuming malice where there might only be mismatch. We can grieve what didn’t work without turning it into evidence that we were foolish to try, or that the other person was fundamentally flawed.

It also eliminates the futile attempt to change other people, because people’s models are built over a lifetime of experiences and are not something we can simply rewrite.

Understanding someone’s model doesn’t excuse hurtful behavior. But it does offer another path forward—one rooted in curiosity instead of condemnation. And when we stop trying to engineer solutions and start wondering about models, something shifts. The story gets more generous. More human. And sometimes that shift can help us see which relationships are worth investing in long term, and which ones will never really work. And perhaps that is the greatest benefit of understanding someone’s model of relationship: it allows us to accept others as they are.

Because not every relationship can be saved. Some models are simply incompatible. The question isn’t whether someone’s model is right or wrong. The question is: do their models align enough with yours to move forward together?

Sometimes they do. Sometimes they don’t.

And sometimes the kindest thing we can do—for ourselves and for others—is to recognize the difference.

About the Author

My name is ES Vorm, PhD. Scientist, former aviator, homeschooling dad. I spent years chasing titles and prestige. These days, I’m just trying to tell the truth—about myself, about others, one story at a time.

This resonates so much, Eric. I’ve learned that truth-telling can feel like an attack to those whose mental models depend on comfort and conformity. When I challenge a story, I’m trying to align the map with the territory, not wound someone. But that mismatch you describe can be devastating when it happens in friendship or community.

Your framing of model mismatch is such a compassionate way to make sense of it. It turns what could feel like rejection into something more neutral, like an incompatibility of maps rather than failure. Thank you for naming it so clearly.

Author is a jerk, blocked....

It is crazy how much the issue is often getting through the interface to the OS when it comes to those personal interactions. Hurts when those friends storm out or fade out when we don't even realize. Not sure it is even different value sets but the exterior motives and interior motives aren't or weren't made clear. Who knows. Sometimes people just suck.